Peptic Ulcer

- Fysiobasen

- Sep 9, 2025

- 4 min read

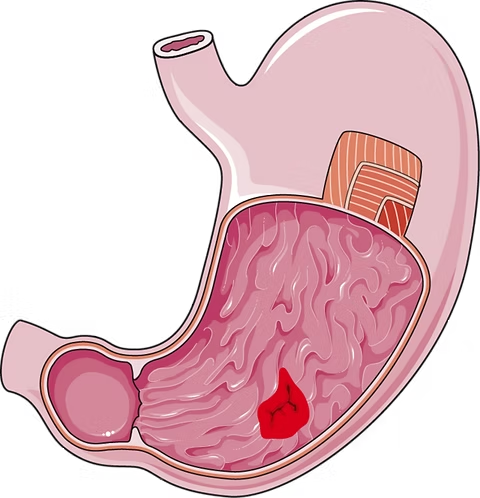

A peptic ulcer develops when the lining of the stomach or duodenum breaks down, resulting in damage to the digestive tissue. Pepsin, an enzyme that breaks down protein, increases the acidity of the stomach and contributes to digestion. Overproduction of gastric acid can eventually destroy the protective mucus in the stomach and duodenum, exposing the tissue to acid damage and leading to breakdown¹.

There are three main types of peptic ulcers:

Gastric ulcer (stomach ulcer)

Duodenal ulcer

Stress-related ulcer

Prevalence and Epidemiology

According to the National Institute of Health, one in ten Americans will develop a peptic ulcer during their lifetime. More than 500 million people are diagnosed each year, and about 4 million cases are recurrent. Ulcers can occur at any age, even in infants, but gastric ulcers are most common after the age of 60 and affect women more often. Duodenal ulcers are most common between the ages of 30–50 and occur more frequently in men than in women. Stress-related ulcers have no clear age distribution but are more often seen in cases of high life stress and after severe injury, such as burns or gastrointestinal surgery. The risk of peptic ulcers is twice as high in individuals with African or Latin American background²³.

Causes

Peptic ulcers may be caused by infection of the mucosa with the bacterium Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), which increases acid production and breaks down the protective lining. H. pylori thrives in the acidic environment of the stomach and intestines and is likely transmitted through food or water contaminated with fecal matter⁴.

Long-term use of NSAIDs (anti-inflammatory drugs), hiatal hernia, folate deficiency, or vitamin C deficiency can also disrupt the balance of gastric juices and make the mucosa more vulnerable. Studies show that psychological stress and poor coping strategies can increase the risk of ulcer development⁵.

Sårstadier og karakteristikk

Ulcer Stages and Characteristics

There are three stages:

Erosion:Superficial damage to the mucosa, 1–2 cm wide.

True ulcer:Deeper damage, often with scarring in the tissue.

Bleeding ulcer:Deep damage with perforation of the stomach or intestinal wall and bleeding. This is a medical emergency that can cause serious complications¹³.

Risk Factors

Age over 50 years

High and regular alcohol intake

Smoking or tobacco use

Family history of peptic ulcer

Previous ulcer or gastrointestinal bleeding

Concurrent use of steroids or anticoagulants

Multiple medications containing acetylsalicylic acid or NSAIDs

Drug hypersensitivity, frequent stomach complaints, or heartburn⁶

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms of peptic ulcer can easily be overlooked in physiotherapy assessments, as many patients do not associate the complaints with the stomach. The patient may present with low back pain without known injury. Pain is often described as a diffuse, gnawing ache that occurs 1–3 hours after eating. It may be relieved by small meals or antacids but returns after a full meal. Large ulcers may obstruct the passage from the stomach to the intestine, causing severe pain, nausea, and vomiting.

Typical additional symptoms:

Night pain while lying down

GERD

Weight loss

Bloating

Belching

Feeling of fullness, poor appetite

Dark stools (melena)

Coffee-ground vomiting

Dizziness

Pain in the right shoulder, often independent of position

Diagnostics

Upper GI series: X-ray with barium swallow to visualize the stomach, esophagus, and duodenum.

Endoscopy: A scope is passed through the mouth into the stomach and intestine to detect ulcers and assess severity.

Blood tests: To detect H. pylori infection.

Treatment and Pharmacological Management

Once the cause has been identified, different medications may be used:

For H. pylori: Antibiotics such as clarithromycin, tetracycline, amoxicillin, metronidazole, and bismuth (Pepto-Bismol).

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs): Omeprazole (Prilosec), lansoprazole (Prevacid), esomeprazole (Nexium) – used in both bacterial and non-bacterial ulcer treatment.

If NSAIDs are necessary: Drugs such as misoprostol or sucralfate may protect the mucosa.

Treatment also involves assessing external factors, reviewing medications, diet, smoking cessation, and alcohol reduction. Surgery may be necessary if the ulcer does not heal:

Antrectomy: Removal of the lower part of the stomach

Hemigastrectomy: Removal of half of the stomach⁷⁸

Differential Diagnoses

Physiotherapists must be aware that peptic ulcers can cause musculoskeletal complaints, often low back pain with unclear onset. Thoracic pain (especially T6–T10) may be referred pain from the gastrointestinal tract. Other conditions with similar symptoms include:

GERD

Diverticulitis

Pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer

Ulcerative colitis

Crohn’s disease

Irritable bowel syndrome

Colon cancer

Refer to a physician if:

Symptoms worsen a few hours after NSAID use

Stomach complaints occur together with muscle/joint pain

Pain in the back/shoulder/sacral area is relieved by meals or bowel movements

Positive McBurney’s point or pain with heel-drop test

Joint pain with newly developed rosacea

Increased muscle tension and pain during treatment⁵

References

Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2009. p. 842–845.

U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. Medline Plus: Peptic Ulcer. Available from: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000206.htm (last accessed: March 15, 2010).

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse. Available from: http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/hpylori/ (last accessed: March 1, 2010).

Helico.com. Available from: http://www.helico.com/

Goodman CC, Snyder TK. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. 4th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. p. 366–408.

American Gastroenterological Association Patient Center. Disease Fact Sheet: Peptic Ulcer Disease. Available from: http://www.gastro.org/wmspage.cfm?parm1=478 (last accessed: March 15, 2010).

National Institutes of Health. DailyMed: Medications. Available from: http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/about.cfm (last accessed: March 30, 2010).

Gladson B. Pharmacology for Physical Therapists. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2006.