Adult-Onset Torticollis (Cervical Dystonia / Spasmodic Torticollis)

- Fysiobasen

- Dec 24, 2025

- 7 min read

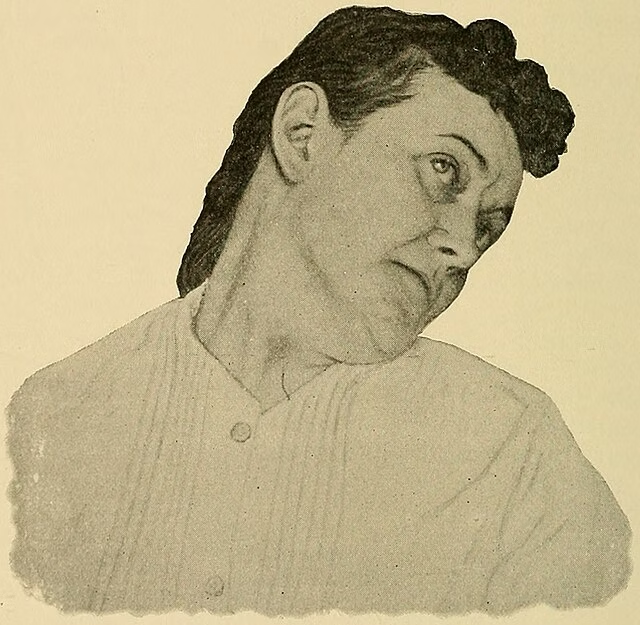

Adult-onset torticollis, also known as cervical dystonia or spasmodic torticollis, is a condition in which the neck muscles become locked in a persistent, involuntary contraction. These contractions often cause twisting, repetitive movements, or an abnormal posture of the neck.[1] The condition can be very painful and cause substantial discomfort. Presentations of torticollis are commonly categorized by cause—acute, congenital, chronic, acquired, idiopathic, or secondary.[2][3]

Epidemiology & Etiology

Idiopathic cervical dystonia (ICD) is the most common form of focal dystonia with adult onset.[4] True dystonia prevalence is hard to pin down. Available estimates suggest a prevalence of primary dystonia of ~11.1 per 100,000 for early onset in Ashkenazi Jews in New York, ~60 per 100,000 for late onset in Northern England, and ~300 per 100,000 in people over 50 in Italy.[5][6][7] Most reported cases fall in the 31–40 age group, suggesting a high prevalence of adult-onset idiopathic cervical dystonia.[5][6][7]

This common disorder is marked by involuntary contractions of neck muscles; in most cases, the cause is unknown. Two possible causes have been studied in depth:

Genetics

Three observations support a genetic contribution to a subset of ICD cases:[8]

In families with childhood-onset idiopathic torsion dystonia, relatives often have focal cervical or segmental dystonia.

Since 1896, torticollis has been observed in siblings, and adult-onset torticollis can occur across multiple generations.

First-degree relatives of patients with focal dystonia have focal dystonia or tremor more often than expected.

Trauma

Trauma may account for 5–21% of cases.[3] Patients frequently report immediate post-injury pain followed by cervical dystonia with near-total neck stiffness within days. Symptoms often persist during sleep. The condition responds poorly to medication and botulinum toxin. None of the trauma cases had a family history of dystonia.[8]

Another possible contributor to ICD is structural brain change. MRI has shown bilateral T2 abnormalities in the lentiform nuclei on quantitative measures (not on visual inspection). Transcranial ultrasound has demonstrated increased echogenicity in the lentiform nuclei, especially in the contralateral pallidum in adult-onset focal dystonia.[6]

Clinical Presentation

Adult-onset torticollis typically presents as rotation of the head or chin toward one shoulder.[9] Repetitive head movements may occur, with spasms that can be intermittent, clonic, or tremulous.[3] One study suggests head tremor (HT) is more common in retrocollis than anterocollis, particularly with earlier disease onset and longer disease duration.[10]

Cervical dystonia can be very painful and can reduce postural control.[3] Vestibular changes—such as hyperreactivity and difficulty perceiving the body’s vertical orientation—may be present.[3] Symptoms can evolve over time.[11] The direction of torticollis is defined by the side the chin points toward; e.g., left torticollis = chin points left.[11]

Differential Diagnosis

Conditions to consider during examination and management:

Parkinson’s disease: May produce head posture resembling torticollis. Usually accompanied by other neurological signs: tremor, unsteady gait, rigidity, dyskinesia.[3][13][14]

Post-traumatic dystonia: History of recent neck injury; often develops within 12 months; estimated in 5–21% of patients.[13]

Wilson disease: Copper overload disorder. In patients <40 years with gradual symptom onset, consider screening.[3][15]

Adult-onset idiopathic torticollis: Gradual onset, often with neck pain (~75%). May also feature jerky movements, spasms, tremor, and shoulder elevation.[3][13][5][16]

Examination

A thorough history and clinical exam come first:

History: Prior episodes, neck pain, headache, birth history, family history, medications, trauma, infection.

Clinical exam: Vitals, posture, soft tissues, muscle atrophy/spasm, movement analysis.

Neurologic screen: Reflexes (C5–C7), myotomes (C4–T1), dermatomes (C4–T1).

Toronto Western Spasmodic Torticollis Rating Scale (TWSTRS) is commonly used to assess dystonic head posture, sensory tricks, duration, and ranges of motion.[3]

Thoracic Provocation Test

Seated rotation (bilateral) to rule out thoracic dysfunction.

Ligamentous Instability

Sharp–Purser and Alar ligament tests to rule out ligament injury.

Active Cervical ROM (typical norms)

Flexion: 45°

Extension: 75°

Lateral flexion: 40°

Rotation: 85°Document limitations. Patients often cannot rotate past midline toward the affected side.

Active Shoulder ROM

Flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal/external rotationObserve gross bilateral movement deviations to rule out shoulder dysfunction.

Palpation

Seated: Upper trapezius, 1st rib, anterior/posterior rib cageSupine: SCM, paravertebrals C7–C1, nuchal line/suboccipitals, mastoid process, C1 transverse processes, C2–C7 spinous processes, C2/3–C6/7 articular pillars

Note trigger-point tenderness or nodules, local spasm and/or tightness. SCM is often particularly prominent.

Joint Mobility

Seated: 1st rib (hypo/normal/hypermobile)Supine:

OA joint (Flex 10°, Ext 25°, side-bend bilat. 5°)

AA joint (Flex 8°, Ext 10°, Rotation 45°)

Articular pillars bilaterally (hypo/normal/hyper)Prone:

Passive intervertebral mobility (bilateral & unilateral)

Record any restrictions or pain.

Muscle Length

Suboccipitals, trapezius, levator scapulae, scalenes, SCMAssess imbalance, resistance to passive motion, end-feel, and pain. SCM is often highly resistant to passive length testing.

Diagnostic Testing

Imaging/labs are not required to diagnose idiopathic torticollis, but can assess tissue integrity when indicated:

X-ray, CT, MRI

Bloodwork if infectious cause suspected[3]Refer to ophthalmology, orthopedics, neurology, etc., as exam findings dictate.

Medical Management

Oral Medications

Typically provide modest symptom relief; often used at low doses (e.g., benzodiazepines, baclofen, anticholinergics).

Anticholinergics show the best effect.

Side effects: dry mouth, cognitive disturbance, diplopia, drowsiness, glaucoma, urinary retention.[3]

Intrathecal Baclofen (ITB)

Effective for generalized dystonia when the catheter is placed above T4.

Clinical studies show significantly reduced dystonia scores and improved quality of life.[3]

Botulinum Toxin

First-line therapy for cervical dystonia. Inhibits acetylcholine release at the motor endplate.

Onset within ~1 week (up to 8 weeks); average duration ~12 weeks.

Target painful/overactive muscles (e.g., SCM, trapezius, splenius capitis, levator scapulae).[8]

Side effects: injection-site pain, dysphagia, dry mouth, weakness in nearby muscles, fatigue.[3]

Surgical Management

Selective Peripheral Denervation

Denervates muscles responsible for abnormal movements while preserving innervation to noncontributing muscles. In a 260-patient series, 88% reported improvement on a 4-point scale (poor, fair, very good, excellent). Muscle selection should be based on clinical exam and EMG confirmation. Best outcomes occur in pure rotational torticollis with mild extension. Possible adverse effects: transient balance issues, temporary dysesthesia or sensory loss in denervated posterior cervical segments, wound infection, and dysphagia.[3]

Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS)

Used for intractable cervical dystonia. Microelectrodes are placed in the GPi (usually bilateral) with targeted microstimulation. DBS yields marked long-term symptomatic and functional improvement in most patients; cervical and generalized dystonia show similar long-term outcomes. Downsides: multiple follow-ups for programming; upsides: reversible, adjustable, and persistent access to the therapeutic target. DBS can reduce oral medication needs. Adverse effects: infection, lead fracture, battery failure, perioral tightening during adjustments. No studies have assessed physiotherapy as an adjunct to DBS.[3]

Both DBS and selective peripheral denervation show gradual improvement with no significant difference overall; DBS may trend toward greater pain reduction.[18]

Physiotherapy Management

Research on physiotherapy for adult torticollis is limited. No randomized controlled trials exist; published work (vibration therapy, progressive muscle relaxation) consists of single-case or small uncontrolled series. Management should therefore follow an impairment-based, individualized approach.[3][8][19][20]

Zetterberg et al. (ABA case series): progressive muscle relaxation, isometrics, coordination, balance/perception training, stretching → short-term improvement; symptoms recurred post-protocol. Half relapsed to baseline VAS by 6 months.[19]

Karnath et al. (single case): vibration aimed at the contracted muscle (5 sec–15 min) allowed relaxation and neutral head position; at 15 minutes the relaxed posture was maintained longer; duration of benefit not reported.[20]

Key challenges: limited mobility, pain, postural control.Because SCM and scalenes (drivers of flexion, lateral flexion, rotation) are often overactive, strengthening antagonists (contralateral SCM, scalenes, neck extensors) can help restore head alignment. If prolonged malposition exists, stretching plus relaxation may restore length; stop if pain rises or no benefit. Mobilization (effective for neck pain) may help with analgesia, provided the patient can sufficiently relax to benefit. Palliative options include soft-tissue mobilization as clinically indicated.

Summary

Given the absence of randomized controlled trials and limited physiotherapy evidence for adult torticollis—and since physiotherapists cannot treat the root cause of idiopathic dystonia—there is no universal standard. An impairment-based plan centered on pain control, mobility, and postural coaching offers the best outcomes. If the therapist suspects Wilson disease or Alzheimer’s disease not evident from history, consider referral.

References:

Kassaye, S.G., De Hertogh, W., Crosiers, D. et al. The effectiveness of physiotherapy for patients with isolated cervical dystonia: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol 24, 53 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-023-03473-3

Sargent B, Lee YA. Child with Congenital and Acquired Torticollis. InSymptom-Based Approach to Pediatric Neurology 2023 Jan 1 (pp. 445-462). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Crowner BE. Cervical dystonia: disease profile and clinical management. Phys Ther 2007;87(11):1511–26.

Dressler D, Kopp B, Pan L, Saberi FA. The natural course of idiopathic cervical dystonia. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2024 Mar;131(3):245-52.

Jankovic A, Tsui J, Bergeron C. Prevalence of cervical dystonia and spasmodic torticollis in the United States general population. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2007;13:411-6.

Albanese A, Barnes MP, Bhatia KP, Fernandez-Alvarez E, Filippini G, Gasser T, et al. A systematic review on the diagnosis and treatment of primary (idiopathic) dystonia and dystonia plus syndromes: report of a EFNS/MDS-ES Task Force. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:433-44.

Camargo C, Teive H, Becker N, Baran M, Scola R, Werneck L. Cervical dystonia: clinical and therapeutic features in 85 patients. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2008;66(1):15-21.

Dauer WT, Burke RE, Greene P, Fahn S. Current concepts on the clinical features, aetiology and management of idiopathic cervical dystonia. Brain 1998;121:547-60.

Kyle S. Dystonia: Far more than just a pain in the neck. InnovAiT. 2024 Sep 17:17557380241284420.

Chen Q, Vu JP, Cisneros E, Benadof CN, Zhang Z, Barbano RL, Goetz CG, Jankovic J, Jinnah HA, Perlmutter JS, Appelbaum MI. Postural directionality and head tremor in cervical dystonia. Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements. 2020;10. doi: 0.7916/tohm.v0.745.

Velickovic M, Benabou R, Brin M. Cervical dystonia pathophysiology and treatment options. Drugs 2001;61(13):1921-43.

Gjennomgått -Trukket

Geyer HL, Bressman SB. The diagnosis of dystonia. Lancet Neurol 2006;5:780-90.

Fleischman DA, Wilson RS. Parkinsonian signs and functional disability in old age. Exp Aging Res 2007;33:59-76.

El-Youssef M. Wilson Disease. Mayo Clinic Proc 2003;78:1126-36.

Costa J, Espirito-Santo CC, Borges AA, Ferreira JJ, Coelho M, Moore P, et al. Botulinim toxin type A therapy for cervical dystonia (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009; (1):CD003633.

Loher TJ, Capelle HH, Kaelin-Lang A, Weber S, Weigel R, Burgunder JM, et al. Deep brain stimulation for dystonia: outcome at long-term follow-up. J Neurol. 2008;255:881-884.

Huh R, Han IB, Chung M, Chung S. Comparison of treatment results between selective peripheral denervation and deep brain stimulation in patients with cervical dystonia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2010;88(4):234-8.

Zetterberg L, Halvorsen K, Farnstrand C, Aquilonios SM, Lindmark B. Physiotherapy in cervical dystonia: six experimental single-case studies. Physiotherapy Theory Pract. 2008;24(4):275-90.

Karnath HO, Konczak J, Dichgans J. Effect of prolonged neck muscle vibration on lateral head tilt in severe spasmodic torticollis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:658-60.