Quadratus Lumborum

- Fysiobasen

- Jan 11

- 9 min read

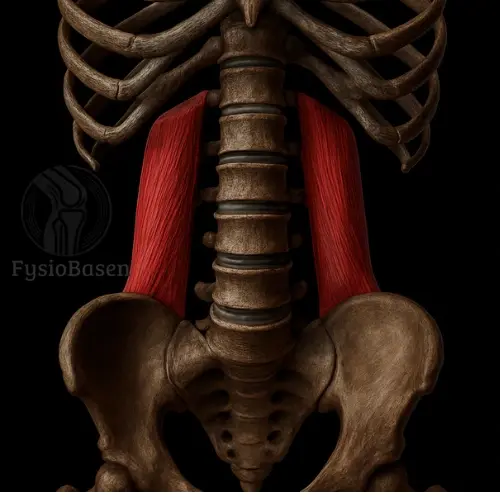

The quadratus lumborum is a deep posterior trunk muscle located in the lumbar region and forms a central component of the posterior abdominal wall. It has a rectangular shape, and its name literally means “square lumbar muscle.” It plays a key role in stabilisation of the lumbar spine and in the thoracic breathing pattern, and is frequently involved in lumbar pain conditions—both as a primary pain source and as a compensatory muscle.

Origin

The quadratus lumborum originates from the iliac crest (posterior portion of the iliac crest) and the iliolumbar ligament.

In addition, some fibres originate from the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis.

This provides the muscle with a robust and stable pelvic attachment, making it well suited to act as a “bridge” between the pelvis and the spine.

Insertion

The muscle inserts on the inferior border of the 12th rib and on the transverse processes of L1–L4.

These attachments allow the muscle both to elevate the pelvis and to draw the rib cage downward, supporting important functions in posture and respiration.

Location and Layering

The quadratus lumborum lies deep within the posterior abdominal wall, directly anterior to the erector spinae muscles and posterior to the kidneys. It is enclosed by the thoracolumbar fascia, which both protects the muscle and provides structural support in coordination with the abdominal musculature.

Laterally, it borders the transversus abdominis, while medially it lies in close proximity to the lumbar spine. Anteriorly, it relates to the kidneys and the psoas major, making the quadratus lumborum clinically relevant in both lumbar and abdominal conditions.

Due to its deep location, palpation is challenging but possible during side bending and light activation, palpating beneath the rib cage and above the iliac crest.

Relationship to the Diaphragm and Breathing

The quadratus lumborum has close anatomical and functional relationships with the diaphragm. It contributes to stabilisation of the 12th rib and prevents it from being pulled cranially during inspiration. In this way, the quadratus lumborum indirectly provides a fixed anchor point for effective diaphragmatic contraction, which is particularly important during physical activity or in individuals with reduced lung capacity.

During inspiration with a fixed pelvis, the quadratus lumborum may assist in depressing the 12th rib and increasing thoracic volume. As a result, it often compensates in cases of reduced diaphragmatic function.

Clinical Observations and Activation Patterns

The quadratus lumborum is well known for its role in hip hitching, i.e. elevation of the pelvis on one side—a compensatory movement frequently observed in leg length discrepancy or limping following injury. Unilateral activation produces lateral flexion of the spine, whereas bilateral activation results in stabilisation and slight extension.

Clinicians often observe increased tone and referred pain from the quadratus lumborum in association with:

Prolonged standing work

Asymmetrical loading of the spine or pelvis

Respiratory dysfunction, where the quadratus lumborum overactivates to assist the diaphragm

Gait patterns with asymmetrical pelvic motion

Function

The quadratus lumborum acts primarily in two ways, depending on whether the pelvis or the rib cage is fixed.

With the Thorax Fixed

Elevates the pelvis on the ipsilateral side (hip hitching).

Important during gait, particularly when the contralateral hip flexors swing the leg forward.

With the Pelvis Fixed

Draws the 12th rib downward and posteriorly, supporting diaphragmatic function during forceful inspiration.

Produces lateral flexion of the spine during unilateral contraction.

During bilateral contraction, contributes to extension and stabilisation of the lumbar spine.

Stabilising Function

Works closely with the deep abdominal muscles (particularly the transversus abdominis) and the multifidus muscles to create lumbar stability, both statically and dynamically.

Is reflexively activated during balance challenges and rotational forces acting on the trunk.

Innervation

The quadratus lumborum receives its nerve supply from the lumbar plexus, specifically:

Subcostal nerve (T12)

Iliohypogastric nerve (L1)

Ilioinguinal nerve (L1)

Segmental branches from L1–L3

These nerves provide motor innervation and are clinically important when assessing neurological function in the region. The nerve roots course in close proximity to the muscle, making the quadratus lumborum sensitive to neurogenic irritation or reflex muscle tension.

Blood Supply

The quadratus lumborum is supplied by several small arterial branches, making it relatively resistant to ischaemic injury:

Lumbar arteries (from the abdominal aorta)

Iliolumbar artery (from the internal iliac artery)

Small branches from the subcostal artery and 11th–12th intercostal arteries

This rich blood supply supports high metabolic activity and underpins the muscle’s ability to sustain prolonged postural loading.

Clinical Significance

The quadratus lumborum is a frequent source of myofascial pain, and trigger points commonly refer pain to:

The lateral iliac crest

The sacroiliac joint

The lower abdomen

The lower thoracic spine

The upper gluteal region

Common Clinical Presentations

Unilateral low back pain without nerve root involvement

Pain during side bending to the contralateral side

Symptom aggravation after prolonged static standing

Pain during breathing, coughing, or laughter when the muscle is hypertonic

Functional Consequences of Quadratus Lumborum Dysfunction

Compensatory gait patterns with lateral trunk sway

Pelvic asymmetry

Increased compressive load on the lumbar spine

Altered breathing patterns, particularly with reduced diaphragmatic contribution

Examination and Palpation

Palpation of the quadratus lumborum is technically demanding and requires clinical experience. The patient is positioned in side-lying or prone. The examiner palpates deeply between the iliac crest and the 12th rib, directing pressure toward the posterior abdominal wall. The lateral and inferior fibres are most accessible.

Muscle tightness may be assessed during side bending, as well as with functional tests such as a modified Thomas test or active hip hitching.

Palpation and Clinical Examination

Palpation of the quadratus lumborum (QL) requires experience and precision due to its deep location behind the abdominal viscera and anterior to the more superficial spinal extensors.

Patient Positioning

Side-lying with slight flexion of the hip and knee

The spine should be gently flexed to expose the contour of the lateral lumbar region

Alternatively, prone positioning with support under the abdomen to reduce lumbar lordosis

Palpation Technique

Place the fingers directly above the iliac crest and move cranially toward the 12th rib

Apply gentle but deep pressure laterally into the abdomen, just lateral to the erector spinae

Ask the patient to lift the pelvis or perform a light upward pull; the QL will then contract and become more prominent

Assess for tightness, tenderness, and side-to-side differences in muscle tone

Signs of QL Dysfunction on Palpation

Palpable tenderness at the origin or insertion

Distinct deep trigger points (often 2–3 primary points)

Referred pain upon pressure (e.g. to the gluteal region, groin, or sacroiliac joint)

Unilateral hypertonicity and muscle shortening

Differential Diagnosis

Pain originating from the quadratus lumborum may mimic several other conditions. It is therefore essential to distinguish between muscular, neurogenic, and visceral causes of lumbar and pelvic pain.

Differential Diagnoses to Consider

Lumbar radiculopathy→ Radiating pain below the knee and positive neurological tests

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction→ Posterior and inferior pain with positive provocation tests

Psoas major tightness→ More medial pain, reduced hip extension, positive Thomas test

Lumbar facet joint pathology→ Pain provoked by rotation and extension, localised to the lumbar spine

Nephritis or renal calculi→ Deep flank pain, haematuria, fever, no muscular tenderness on palpation

Appendicitis or retrocaecal inflammation→ Right-sided abdominal pain that may mimic QL pathology

When in doubt, organic pathology must always be excluded before diagnosing a musculoskeletal condition.

Physiotherapeutic Treatment and Activation

Treatment of QL dysfunction should always be part of a comprehensive assessment of the pelvis, hip, and lumbar spine. Interventions should be directed toward:

Relaxation in cases of hyperactivity

Strengthening in cases of instability

Mobility in cases of unilateral shortening

Passive Interventions for Pain or Tightness

Myofascial release and trigger point therapy

Needling techniques (IMS or dry needling) for deep trigger points

Heat therapy to promote muscle relaxation

Mobilisation of the thoracolumbar junction

Diaphragm-focused breathing for indirect relaxation (QL often overactivates during dysfunctional breathing)

Active Exercises for Strength and Control

Side-lying hip hitching→ The patient lies on the side and lifts the upper pelvis without using the leg muscles→ Emphasis on control and isolation

Bird dog with rotation and side-bending→ Increased QL activation when the arm and leg are lifted and the trunk is rotated→ Controlled execution with focus on lumbar stability

Standing hip hike on a box→ Standing with one foot on a box, lifting the opposite side of the pelvis→ Promotes functional QL activation

Side plank with pelvic lift→ Static and dynamic control with high load on the ipsilateral QL

“Bamboo exercise” (dynamic side bending)→ Use of a barbell or dowel to actively bend side to side→ Effective for mobility and control of the lateral bending axis

Rehabilitation Principles

Rehabilitation of the quadratus lumborum should include:

Restoration of symmetry between the right and left sides

Integration of QL training with breathing techniques and pelvic control

Addressing underlying factors such as leg length discrepancy or hip dysfunction

Combining strengthening and stretching for balanced muscle use

Early inclusion of functional exercises to prevent compensatory patterns

In long-standing QL dysfunction, symptoms may become self-perpetuating through compensatory movement patterns. Breaking this cycle requires specific and patient guidance.

Exercises for the Quadratus Lumborum

The quadratus lumborum primarily acts as a lateral stabiliser of the lumbar spine and plays a key role in side bending, pelvic elevation, postural control, and diaphragmatic stabilisation. It is most active when the body must control lateral forces or compensate for instability in the pelvis and lumbar spine.

Exercise selection should be based on:

The need for strength, control, or relaxation

Unilateral versus bilateral function

Whether the QL acts as a prime mover or a stabiliser

1. Side-Lying Hip Hitching

Purpose: Isolated activation of the ipsilateral QL in a shortened position

Execution:

The patient lies on the side with hips and knees slightly flexed

The upper leg remains relaxed; the pelvis is lifted toward the ribs

Hold for 3–5 seconds, then return slowly

Focus: The QL shortens and activates concentrically. Ensure the patient does not compensate with the gluteal or hamstring muscles.

Evidence: EMG studies demonstrate high QL activation in this position, especially when performed slowly with isolated movement (McGill et al., 2009).

2. Side Plank With Hip Lift

Purpose: Increase QL strength and endurance as part of core stability

Execution:

Standard side plank from knees or feet

The pelvis is lowered in a controlled manner and lifted back to neutral

Can be progressed using resistance bands

Focus: The QL works eccentrically and concentrically during pelvic lowering and lifting. High neuromuscular control is required.

Evidence: Several studies (e.g. Ekstrom et al., 2007) show that dynamic side plank variations elicit higher activation than static holds, with particularly high QL activity during lateral instability.

3. Bird Dog With Lateral Flexion

Purpose: Dynamic control and integration with the spinal extensors

Execution:

From quadruped, lift the opposite arm and leg

Bring elbow and knee toward each other with diagonal rotation

Add a gentle lateral flexion before returning to neutral

Focus: The QL activates to prevent collapse of the lumbar spine, challenging both stability and coordination.

Evidence: This variation produces higher QL activation than the standard bird dog, particularly on the weight-bearing side (Borghuis et al., 2008).

4. Standing Hip Hike on a Step

Purpose: Functional QL strength and control in a weight-bearing position

Execution:

Stand with one foot on a step, the other hanging freely

Lift the hanging side by elevating the pelvis

Hold for 2 seconds, then lower slowly

Focus: Isolates the QL responsible for elevating the pelvis on the unsupported side. Also activates the gluteus medius and lateral core musculature.

Evidence: Commonly used in rehabilitation of pelvic instability and low back pain (Richardson & Jull, 1995), providing high QL activation without excessive spinal load.

5. Side-Lying Leg Raise With Rotation

Purpose: Combined activation of the QL and oblique abdominal muscles

Execution:

The patient lies on the side with the forearm supporting the upper body

Lift the upper leg while simultaneously rotating the trunk backward

Perform slowly and with control in both directions

Focus: Creates transverse loading of the QL through combined side bending and rotation.

Evidence: Lower load than side planks but suitable early in rehabilitation. EMG analyses show activation of both the QL and internal oblique muscles (Cresswell et al., 1994).

6. Resistance Breathing (QL–Diaphragm Interaction)

Purpose: Indirect QL activation through deep core and respiratory muscles

Execution:

The patient lies supine with knees bent

Performs slow, controlled breathing against resistance (e.g. PEP device or pursed-lip breathing)

Focus on expanding the lateral rib cage and creating pressure into the flanks

Focus: Enhances coordination between the QL and diaphragm, particularly important in chronic low back pain.

Evidence: Widely used in respiratory physiotherapy and lumbar instability rehabilitation; shown to reduce QL hyperactivity (Hodges et al., 2005).

How to Choose the Appropriate Exercise

Selection should be based on:

Relaxation: breathing, massage, mobilisation

Early activation: side-lying hitch, bird dog

Strength: hip hike, side plank

Functional integration: standing rotations, asymmetrical carrying

Endurance: prolonged side plank holds, breathing control

All exercises should be supervised by a physiotherapist and adjusted to the individual’s functional level. For optimal outcomes, the quadratus lumborum should never be trained in isolation over time but integrated with pelvic control, thoracolumbar mechanics, and hip stability.

References

Drenckhahn, D., & Waschke, J. (2008). Taschenbuch Anatomie (1st ed.). Urban & Fischer / Elsevier.

Schünke, M., Schulte, E., & Schumacher, U. (2007). Prometheus – Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System (2nd ed.). Thieme.

Fors, S. (2007). Why We Hurt – A Complete Physical and Spiritual Guide to Healing Your Chronic Pain. Llewellyn Publications.

Cael, C. (2010). Functional Anatomy: Musculoskeletal Anatomy, Kinesiology, and Palpation for Manual Therapists. Wolters Kluwer.

Moore, K. L., Dalley, A. F., & Agur, A. M. R. (2014). Clinically Oriented Anatomy (7th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Netter, F. (2019). Atlas of Human Anatomy (7th ed.). Saunders.

Palastanga, N., & Soames, R. (2012). Anatomy and Human Movement (6th ed.). Churchill Livingstone.

Standring, S. (2016). Gray’s Anatomy (41st ed.). Elsevier Churchill Livingstone.